I recently found myself truly surprised. A scary Krampus was depicted on red and black beer cans. They were for sale during the winter holiday season at the Brunswick Brewing Station Brewery in Maryland. There the row of six packs of dark stout beer, spiced with Habanero Chiles, brought me back to almost forgotten childhood memories. The horned Krampus was also depicted on the labels of brown long necked bottles beer bottles, not far from ancient wooden 40 gallons bourbon barrels, and near the Brewery’s food and beer ordering counter. After many years of adult life, the ugly horned Krampus image and its meaning did not scare me anymore. I knew that inside the Brunswick Smoketown Brewing Station I felt safe. I was surrounded by smiling beer drinking customers and enthusiastic Thursday Trivia Night winners. The devilish character did not ask me to recite the multiplication table. My friends Bob, Michelle, Carolyn, Bayley, and Dani were there. They had stopped by the Brunswick Brewing Station to attend Sarah’s Trivia’s Night, eat hot dogs, and soft Bavarian Pretzels. Around me, laughter, guessed answers, scored points, and my own personal celebration of the ancient American German heritage. For late comers, the Krampus Stout with Habanero I was told was sold out fast. Hopefully the brew will return next holiday season with Brandon, the “Brewer Meister” who maybe will increase his production keeping in mind how good his stout has been.

WHO IS KRAMPUS AND HOW DID THAT DARK SCARY RASCAL MOVE FROM THE MIDDLE EAST TO EUROPE AND TO AMERICA

The Krampus of many Germanic tales has many names in Europe and America. Europeans call him de Zwarte Piet (Black Peter for the Dutch) and Knecht Ruprecht (Ruprecht the servant for Germans). North Americans know him as Black Peter, Bellsnickler, Pelz Nikel, and Krisskringle. His origin dates back to the first and second Crusades (XI century and on). During this time, Muslim Moors fought the Christians over the control of Jerusalem. They also battled for control over the spice trade routes. In the name of the fight between good and evil, Krampus became associated with the dark Moors. These Moors fought against those who wanted to keep Jesus’s land open to Christians. Over time, the dark, scary character became a symbol of Christian wars. Saint Nicholas, Christian Bishop of Myra, represented goodness against evil.

WHAT ABOUT SAINT NICK ?

The beginnings of the cult of Saint Nick, also known as der Heilige Nikolaus or Saint Nicholas, dates back to the times when the Christian bishop’s remains of Myra arrived in Bari, an Italian port city, around 1095. In honor of the miracle worker, the bishop’s remains were placed in a lavishly gold decorated crypt in the Cathedral of Bari. This was done with the blessing of Pope Urban II. From there, knights, travelers, and pilgrims who departed or returned from the Holy Land became accustomed praying for healing and good fortune. Thus, from Turkey to Italy, and from Bari to Nordic regions, Saint Nicholas’s fame moved beyond the Italian Alps. With Catholic and Protestant immigrants, it spread throughout Central Europe and finally reached North America. With Dutch and Germanic immigrants the cult survived with or without Krampus, later renamed the Bellsnickler, the Krisskringle, the Black Peter or the Pelznickl.

A SHORT STORY ABOUT THE TWISTED “BREZEL” (German for Pretzel)

According to “Brezel” history, the twisted baked goods became famous during the European Middle Ages. “Brezel” were served especially during fasting banquets. One of the earliest depictions of the twisted bread dates back to the 11th century. It shows “Brezel” being served during a communal meal shared by the religious brothers of the Austrian Saint Peter Convent (Kloster Sankt Peter) of Salzburg. By 1276, Augsburg’s German law regulated the commerce of baked goods in a new way. It allowed the “Brezel” not only to be prepared for nobility banquets and fasting meals but also sold to commoners. After that, “Brezel” were commonly served either during New Year-Epiphany-Lent days or to celebrate Memorial Days. By 1726, in the German town of Mannheim, a good Baeckermeister (Baker Master) needed not only be able to bake bread but also “Brezel.” And, legends reported that the shape of the twisted bread represented the joined arms and hands used to pray by the convent monks (Die Geschichte der Brezel: Wo und wann wurde das Kultgepaeck erfunden? – https://www.brotexperte.de).

RECIPE: HOW TO MAKE 2 AMERICAN “OLE” SOFT PRETZELS

Authentic Bavarian pretzels use lye to create that classic golden brown crust. However, you can also use baking soda instead of lye. Baking soda is safe and easy and will result in a golden crust. For an extra shine, brush the top of the pretzel with egg wash. Beat one egg with 1 tablespoon of water to make the wash. Alternatively, spray with water to give it a glaze when it is still hot.

Heat either a baking stone or a baking sheet in an oven to 450-500° F (230° C). In a large mixing bowl, stir together barley malt syrup (or 2-3 Tbsps of molasses), dry yeast (2 1/2 tsp or an envelope), and 1½ cups lukewarm water. Let the mixture sit for about 10 minutes. Wait until it bubbles or appears foamy. If the mixture doesn’t foam, either the water was too hot or the yeast is old.

To the mixture in the bowl, add 3 Tbsps. butter, 4 cups all purpose unbleached flour, and 1/4 tsp. kosher salt and stir for about 6 minutes or until obtaining a dough.

Once the dough seems firm enough and workable, transfer it to a lightly floured surface. Knead for an additional 8 minutes. Continue until the dough is smooth and elastic. Cut the dough in half, work each piece into a 4′ long rope, about 1″ thick. Transfer each rope on a large sheet of parchment paper. Shape the dough into a pretzel by picking up both ends. Cross one end over the other and twist them into the shape of the classic pretzel. Attach each end to the sides of the pretzel. Repeat the same with the other half dough. Cover the pretzels with a damp tea towel and set them aside to rest and rise for 20-30 minutes. While the soft pretzels rise, combine 2 Tbsps. of baking soda and 1 cup of water in a small saucepan and bring to a simmer over low heat. Set aside the baking soda. Once the pretzels have risen, brush them with baking soda wash to make them shiny.

HOW AND WHEN DID ST. NICK, WITH OR WITHOUT KRAMPUS, MOVE TO MANHATTAN, NEW YORK, PENNSYLVANIA, WISCONSIN AND MARYLAND?

The good St. Nick and and the scary Krampus likely moved to North America after the European Council of Trento (1545-1563). Both characters arrived either with Germanic and Dutch Protestant or Catholic Austrian migrants. Both groups of immigrants brought to the New World their traditions with renamed characters. The Dutch introduced Zwarte Piet (black Peter) and Sinter Klaas (Saint Nicholaus) to Manhattan first. Later, they brought them to the Pennsylvania Dutch regions. In Manhattan Dutch founded a Knickerbocker society in honor of the saintly bishop (see Washington Irving in 1809 describing the event).

With the melting of immigrant groups two characters became known individually with various names; these names included: der Weihnachtsmann (the Christmas Man), Santa, Father Christmas, Saint Nick, and Bellsnickler (the Nick with bells), the Pelznickl (the Nick with fur), Krisskringle (distortion of Kristkindl [baby Christ]), Knecht Ruprecht (Servant Rupert), and Krampus.

By 1822, in the United States, appeared the famous poem by Clement Clark Moore honoring a St. Nicholas –The visit of St. Nicholas by Clement Clarke Moore (Random House Publications 1983).

” Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house. Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse; The stockings were hung by the chimney with care, In hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there; The children were nestled all snug in their beds; While visions of sugar-plums danced in their heads; And mamma in her ‘kerchief, and I in my cap, Had just settled our brains for a long winter’s nap, When out on the lawn there arose such a clatter, I sprang from my bed to see what was the matter.”

“Away to the window I flew like a flash, Tore open the shutters and threw up the sash. The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow, gave a luster of midday to objects below, when what to my wondering eyes did appear, but a miniature sleigh and eight tiny rein-deer, with a little old driver so lively and quick. I knew in a moment he must be St. Nick. More rapid than eagles his coursers they came, And he whistled, and shouted, and called them by name: “Now, Dasher! now, Dancer! now Prancer and Vixen! On, Comet! on, Cupid! on, Donner and Blitzen! To the top of the porch! to the top of the wall! Now dash away! dash away! dash away all!”

“As leaves that before the wild hurricane fly, when they meet with an obstacle, mount to the sky; so up to the housetop the coursers they flew with the sleigh full of toys, and St. Nicholas too— And then, in a twinkling, I heard on the roof the prancing and pawing of each little hoof.”

“As I drew in my head, and was turning around, down the chimney St. Nicholas came with a bound. He was dressed all in fur, from his head to his foot, and his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot; A bundle of toys he had flung on his back, and he looked like a peddler just opening his pack. His eyes—how they twinkled! his dimples, how merry! His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry! His droll little mouth was drawn up like a bow, and the beard on his chin was as white as the snow; The stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth, and the smoke, it encircled his head like a wreath; He had a broad face and a little round belly that shook when he laughed, like a bowl full of jelly. He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf, and I laughed when I saw him, in spite of myself; a wink of his eye and a twist of his head soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread; He spoke not a word, but went straight to his work, and filled all the stockings; then turned with a jerk, and laying his finger aside of his nose, and giving a nod, up the chimney he rose; He sprang to his sleigh, to his team gave a whistle, And away they all flew like the down of a thistle… But I heard him exclaim, ere he drove out of sight— “Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good night!”

“POUR HOUSE TRIVIA” AT THE BRUNSWICK SMOKEHOUSE BREWERY STATION IN MARYLAND – EVERY THURSDAY NIGHT AT 6 P.M.

The Smokehouse Brewery Station is located at the heart of downtown Brunswick, Maryland. The venue offers excellent beers. It also features a popular “Pour House Trivia Thursday Night.” Over time, good beer and events have changed the old Maryland railroad town. They have given it a new and interesting social meaning. The Brewery has revitalized Brunswick’s 1948 fire station. In 2015, it became a full-fledged brewery. The Smokehouse Brewery Station is at mile marker 55 of the C & O Canal. It overlooks the Potomac River. The Brewery is usually open every day from 3 p.m. on, on Saturdays and Sundays from Noon on for beer and food and hosts comedy, music, and trivia events. The Pour House Trivia Nights take place every Thursday from 6 p.m. to about 8 p.m. Over the Christmas season Brunswick’s Smokehouse Brewery in Maryland served and sold also its very special KRAMPUS STOUT SPICED WITH HABANEROS

READING ABOUT THE AMERICAN SANTA, SAINT NICHOLAS, KRAMPUS, KNECHT RUPRECHT, SWARTE PIET, SINTERKLASS, ST. NICK, BELLSNICKLER, PELZ NICKL, KRISSKRINGLE:

Christmas Customs and Traditions by Clement A. Miles, published by Dover in 1976 and Christmas in Pennsylvania – A Folk Cultural Study by Alfred L. Shoemaker with introduction by Don Yoder, published by the Pennsylvania Folklore Society, Kutztown, Pennsylvania, in 1959

WHERE TO TASTE SMOKEHOUSE BREWING STATION’S BEERS: Visit 223 West Potomac Street, Brunswick, 21716 Maryland. FOR DETAILS ON “POUR HOUSE TRIVIA” NIGHT OR OTHER EVENTS AT THE BRUNSWICK SMOKETOWN BREWERY STATION: Call Tel. 301 834 4828 or 301 969 0087 – http://www.smoketownbrewing.com

FROM BERLIN TO BRUNSWICK ALONG THE BANKS OF THE C& O CANAL IN MARYLAND

“Berlin’s” settlement dated back to the 18th century. During this time, a ferry was established in Maryland along the banks of the Potomac River. The ferry was set in place at the “German Crossing.” This crossing was established in 1731 to facilitate the movement of goods between Maryland and Virginia. By 1834, Leonard Smith purchased land near the ferry on the Maryland side. The construction of the C&O Canal and the B & O railroad passed “Berlin” on the way to Cumberland. This route made the settlement an important stop for goods and people. By 1845 Charles M. Wenner built a flour and grits (German Griess) mill on the town’s land. By 1890 the town of Berlin was renamed Brunswick. This change was to avoid mail delivery confusion with another Maryland settlement also called Berlin. By 1910 the newly named town of Brunswick counted 5,000 inhabitants. It was a lively freight and railroad town. The mill was located at lock 30 near the canal. A well-run system moved goods and people from the east to the west and back…

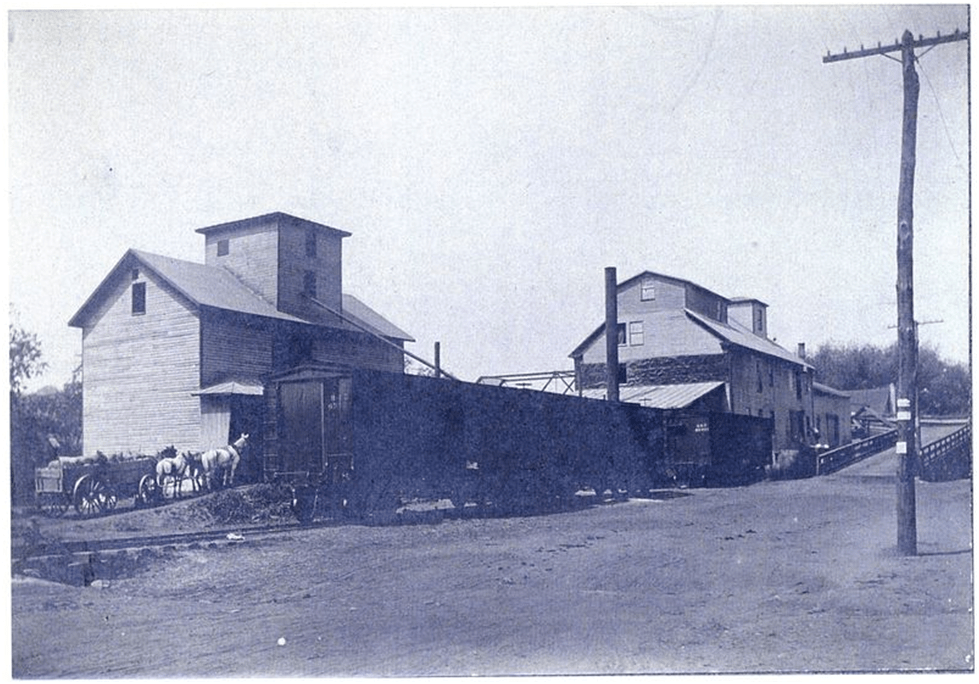

The grain elevator (left) and flour mill (right) at Lock 30 built in 1845 by Charles M. Wenner; c. 1900. The lock was behind these structures. The ramp leading to the old Brunswick Bridge is visible to the right on this old photograph. After the widow of C.F. Wenner, son of Charles M. Wenner, sold in 1882 her interests to the business, the old flour and grist mill was run by B.P. Crampton & Co. (excerpt from a Historic Resource Study – Brunswick, MD – Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park by Edward D. Smith -Denver Service Center, Historic Preservation Team, National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior, Denver, Colorado – January 1978 and https://brunswick.md.gov 1/13/2025).

GERMANIC ROOTS OF AMERICAN BRUNSWICK ?

Up to the 12th century, a Saxon noble family ruled the German region of Braunschweig. Then, through marriage, the area came under the control of the House of the Welfs nobility. Henry the Lion belonged to the House of the Welfs. Once he became duke of Saxony, Braunschweig was the capital of the region. The city capital served as the capital to both Saxony and Bavaria. When Henry the Lion refused military aid to the German Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (Red Beard), the ruler of Braunschweig was banished from Germany and went into exile in England. There Henry the Lion had ties through his marriage to Henry II of England’s daughter Matilda, sister of Richard the Lionheart.

From the early 13th until the 17th century, the German state region of Braunschweig, also known as Brunswick, remained an important member of the Germanic Hanseatic League. This league had commercial centers throughout Europe, including London. Braunschweig with its capital, also named Braunschweig, or Brunswick by the English was over several historic generation a vital center of German European center of trade and commerce and European political power. First, Braunschweig (Brunswick) was the capital of the Principality of Braunschweig Wolfenbuette (1269–1432, 1754–1807, and 1813–1814). By the year 1600, Braunschweig as a capital was the seventh largest city in Germany. From 1814 until 1918 Braunschweig served as the capital of the Duchy of Braunschweig. Finally, Braunschweig became the Free State of Braunschweig (1918-1946). This change occurred shortly before the end of World War II.

After the arrival of the Pilgrims to North America, many Germans sought opportunities in the United States. Newly arrived Germans settled in states such as Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, and Virginia. They also settled in Wisconsin, Texas, and Maryland. In some of these states, Germans founded towns with German names such as Manheim, Dunker, and Berlin. After 1790, 33% of Pennsylvania’s inhabitants were of German origin. In Maryland, 13% of the inhabitants had a German background. Today, more than 40 million Americans have German ancestry. This is more than any other group except the British (CRBEHA – WSU Libraries Digital Collections and Wikipedia).

Brava! Sempre interessante il tuo blog